Meet Joanne. Jo has a nasty and persistent foot fungus, so agrees to take part in the trial of a new fungal cream. She is given a questionnaire and asked to rate her fungal problem on a 0-10 scale at the start of the trial, and then again when it’s over. At that point, we want to know two things. Firstly, how much has her condition changed? More importantly, what, for Joanne, would represent a meaningful change?

What is a meaningful change? This question is at the heart of all the trials that we run. It sounds wonderfully simple; however, getting a useful answer can be tediously difficult.

People use many techniques to do so. Some, including the most common, could charitably be described as ‘unburdened by impartiality’. There are some useful methods that can help. For instance, here is something my colleagues and I wrote that generated a lot of interest, and here’s a whole special issue that I co-coordinated on the subject.

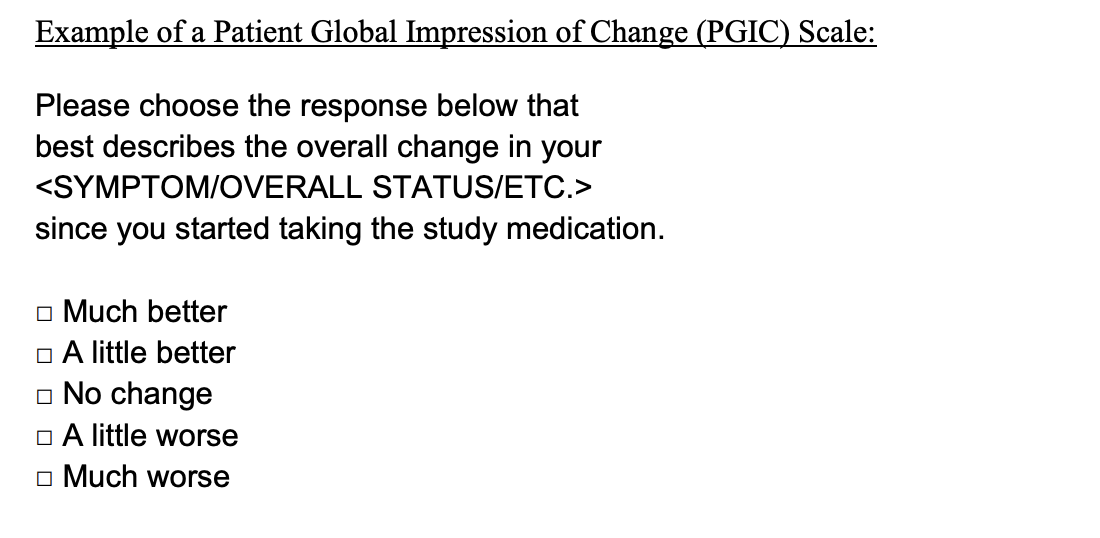

The problem is that all of these techniques (even the best) are ‘anchor-based’. Anchor-based methods rely on a reference measure, known in the business as a ‘single item’, which is usually a variation on the same question: “Since you started the study treatment, how you doin’?”:

This question enables us to sort the patients into groups: those who feel they’ve worsened, those who feel they’ve improved and those who haven’t noticed a change. We can then compare the average scores of the last two groups on the original questionnaire, and that score difference forms the basis of the meaningful change threshold.

This all sounds very neat. Unfortunately, there’s an elephant in the room. She’s sitting right there, at the top of the single item above. She is the Global Impression Scale.

The Global Impression Scale implies that this single item sits apart from the questionnaire we care about; that in its five-point wisdom it is all-seeing and all-knowing, entirely without flaws, and that it gives us the absolute truth about a person’s change over time. Unfortunately, noise or error can creep into single item measures at multiple points.

One of the most obvious problems is that different people tend to approach these questions in different ways. Jo may focus on the increased crustiness of her fungus over the last week, while Graham is more worried about the fact that his changed color overnight, even though it has been oozing less frequently since Tuesday. Then there is the long list of things that Jo and Graham don’t know about their own condition. Far from being the gold standard, it turns out that these single items have the same reliability issues as any questionnaire.

In that case, how reliable can a single item be? More to the point, why should you care? Well, if your single item ‘anchor’ is the foundation of your meaningful change derivation, then you need know if it is all noise and no signal, because it directly relates to how much you can trust the meaningful change number that comes out of your analysis.

Luckily, we can use cool methods such as factor analysis to find out how reliable a single item measure is. This isn’t as straightforward as a correlation or a mean, but it does give you a good read on the strength of your item. It can be used in the preliminary phases of research to build a single item you can trust, and later, you can use it to give you confidence in your results.

Hang on though. What if you do this and find out that your single item measure isn’t very good? It’s an excellent question. It really comes down to psychometrics being one step in a longer process that starts with clear and thoughtful design of single items, rather than simply the re-using of templates like the one above. Those considerations, however, are for another post.